Nic Brierre Aziz’s video, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies), took home first place in the 2020 edition of Louisiana Contemporary, Presented by The Helis Foundation. In this interview, we learn more about Aziz, his development as an artist and his current work.

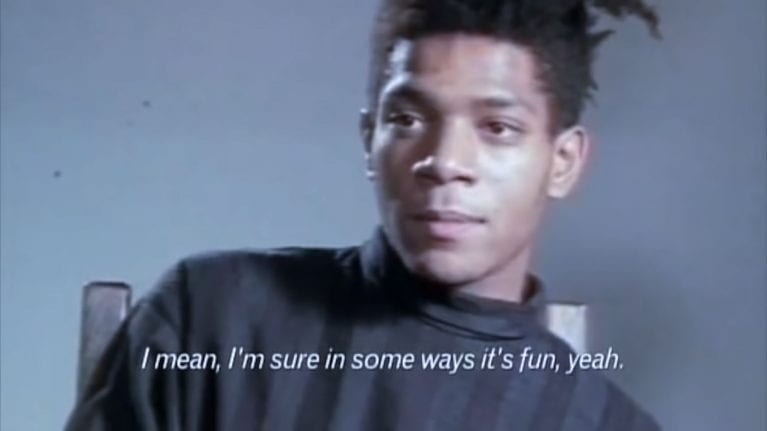

Nic Brierre Aziz, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies) (still), Video

Q: You mentioned in your artist statement that one of the costliest natural disasters (Hurricane Katrina) liberated you from the “mental captivity” you were experiencing and changed your life for the better. Were you creating art prior to this turning point in your life? Or was it not till after that you were able to find your voice as an artist?

A: Prior to this, I think the most art I was creating was poetry here and there. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was also influenced by my Haitian heritage and growing up around an abundance of Haitian art and artists. I also played piano and saxophone for 11 and 4 years respectively and had the honor of studying music under greats like Frank Richard and Kidd Jordan during different points of my childhood – so creativity was always around me. After Katrina, I was really able to start to find my voice and that was mostly the result of a new environment, Shreveport, which included going to public school for the first time in my life. It was also the first time in my life that I didn’t have to wear a uniform to school every day, so I think I ended up making up for all my years of repressed self-expression in a very serious way over those three years I was there.

Q: Have you always wanted to be an artist?

A: Definitely not. I honestly didn’t even see it as a legit pathway until maybe 5-6 years ago – despite growing up around an abundance of art and artists. For some reason, it just wasn’t projected as a viable option. My mom is from Haiti and I think the fact of her being an immigrant also affected that deprioritization of art as a legit career path. For a long time, it was a very “lawyer, doctor, businessman” type frame that I was working within. Also the pathway for an artist or someone working in the arts is so abstract, individualized and opaque – and as a result, hard for anyone to understand which just additionally impairs one’s ability to see it as a viable possibility.

Q: How would you describe your art? What are you trying to convey with your work?

Nic Brierre Aziz, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies) (still), Video

A: This is something I’ve struggled with in the past, but I recently feel like I’ve determined a succinct way to do this. I’ve established that my work can be described as “historical-pop cultural assemblage.” Assemblage is at the root of pretty much all of my works to date. Whether a mixed media piece or video piece such as Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy, I see myself assembling and remixing stories and materials that already exist within the universe to create something with new meanings and layers. I also think there is always a historical and/or pop cultural element to each of my pieces – whether that’s a KFC bucket or Off-White shoes or shackles used on enslaved Africans. Narratives regarding how Black people have been oppressed in this country is also a prominent theme within my work, and I’ve actually been sitting with the thought recently that even slavery was “pop culture” at one point.

Q: What do you think makes the New Orleans art scene special?

A: New Orleans’ art scene is so special for so many reasons – but one of the main ones that sticks out to me is its rootedness and lack of pretentiousness. I’ve heard about other scenes like New York or Los Angeles and how they have a lot of that pretentious air. I think so much of it in those types of scenes is the product of people having different motivations and intentions than artists have here. I think because New Orleans is such a cultural nexus and so many people here are artists in their own right, those who take on the actual term “artist” professionally are people who just do their work and aren’t operating from a place of greed or pretentiousness when making or doing what they do. I think this concept is also just a part of the overall culture and way of life in New Orleans. We just go with the flow so much here. I think that’s also a big reason why major celebrities love coming here. They can come here and just be without as much of the hoopla. We just exist here and do our thing and treat people as their human selves and don’t get as caught up in who they might know, or what huge accomplishment they have, or what huge movie they’ve been in, or whatever. We just let everybody be who they want to be.

Q: How does the city influence what you do?

A: I think it’s hard to think of a way that New Orleans doesn’t influence what I do. The older I get, the more thankful I am to my parents for meeting here and giving my soul the ability to call this place my home. I believe I especially carry so much of New Orleans with me when I travel across the world and I think it’s gotten to a point where it’s just so natural – like breathing. One of my favorite things is going places and sharing New Orleans’ beauty with new people I meet – and I have gotten in a habit of explaining this beauty by emphatically telling these people how “New Orleans is the most culturally rich city in North America.” I’ve learned that peoples’ reaction to that statement can tell me a lot about my ability to go further with them. While that is a huge statement, it is so seeped in fact and I love being able to absorb these endless layers of culture here daily and being someone who gets to frequently share those layers with people across the world. I truly think it’s impossible to exist in a city like this and not engage in art and creativity in some way. Literally wherever you go, wherever your head turns, you will experience world class culture. Even if you don’t consider yourself an artist, when you live in a city like this, you’re an artist in some form or fashion. I’ve lately had people be surprised when they find out that I didn’t go to art school – and my response is usually, “I didn’t go to art school. I was born and raised in New Orleans.”

Nic Brierre Aziz, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies) (still), Video

Q: How has the rise of social media impacted the way you connect with people as an artist?

A: I go back and forth with my feelings about social media. There are times when I wish it didn’t exist how it did and that I could just take myself off and live without it. But I think we’re unfortunately past a point of being able to live “without” it – especially as artists at this moment in human history. I’ve even noticed many artists who existed and were successful before social media was what it is now are now trying to determine how to effectively utilize it for their practice. At the end of the day, I think it provides us all, and especially artists, ways to directly learn, connect and share ourselves in ways that no other medium can. That’s honestly how and why I started using Instagram – simply to find artists and share their work and you can still see that thread on my profile today. My first major group exhibition that I curated was in 2017 and entitled Alien vs Predator – and of the 26 artists featured in the show, 12 were from outside of New Orleans and I found almost all of them via Instagram and just DM’d or emailed them from there. Social media is such a powerful tool and I’m excited to see how we collectively start to use it in more useful and intentional ways.

Q: How has your work, if at all, changed from your first works? Where do you see your work going in the future?

A: I think I’m just constantly becoming more focused in what I want to express and how my natural interests and experiences relate to those expressions. For example – just being able to now fully acknowledge the pop cultural influences in my work. I am fully a product of being deeply influenced by and having a great affinity for pop culture. Artists like Pharrell and Kanye West influence my artistic practice as much, if not more, than artists like Basquiat or Kerry James Marshall or Hank Willis Thomas. I’m just as much of a historian as I am a child of the 90s who loves the idea of a remix. I’d like my work to become more material and sculptural based. I see myself getting more into using found materials to express my ideas through more mixed media and sculptural installation types of works. I also see my work becoming more African Diasporic focused and connecting.

Q: Are you excited about any upcoming projects you’re working on?

A: There are two projects that have me really excited. In the immediate future, I’m working on a piece and project that will be a critique on one of our city’s most prominent symbols. I’m hoping it can be a project that just illuminates an underdiscussed truth in an effort for us to more equitably and collectively decide how we move forward with it. In the less immediate future, I’m extremely excited about continuing my work with my Andy Warhol Foundation fellowship. This was a fellowship that I was awarded in January and it’s a two year curatorial fellowship to explore Haiti’s cultural influence across 9-10 countries within the African Diaspora. I will be traveling to these places, speaking with artists, scholars and cultural workers in an effort to learn more about Haiti’s influences on these places with the end goal of curating a large group exhibition that would be presented here in New Orleans in now 2023. I was supposed to be traveling this year and next, with the exhibition opening in 2022 – but COVID has obviously forced the timeline back a bit. I’m so excited for this opportunity and the chance to explore how connected New Orleans is to so many other deeply African-influenced capitals of the Caribbean and Americas.

You can see Aziz’s work, Aziz, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies), in Louisiana Contemporary, presented by the Helis Foundation, at Ogden Museum through February 7, 2021.

About Nic Brierre Aziz

Nic Brierre Aziz is an American-Haitian interdisciplinary artist and curator born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. His current practice is deeply community focused and rooted around the utilization of personal and collective histories to reimagine the future. He has worked extensively leading community engaged projects throughout New Orleans, with entities such as the Office of Mayor Mitch Landrieu, Antenna, The Joan Mitchell Center, YAYA, the Arts Council of New Orleans and Prospect. In addition to his personal artistic practice, he currently serves as the Community Engagement Curator for the New Orleans Museum of Art. He has contributed to publications such as HuffPost, Burnaway and AFROPUNK, and his work has been featured by The Oxford American, The Associated Press and The Alternative UK. He is a recipient of several notable artist residencies and fellowships and most recently was selected as a 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Curatorial Fellow. He obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Morehouse College and a Master of Science degree from The University of Manchester (UK).

Nic Brierre Aziz is an American-Haitian interdisciplinary artist and curator born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. His current practice is deeply community focused and rooted around the utilization of personal and collective histories to reimagine the future. He has worked extensively leading community engaged projects throughout New Orleans, with entities such as the Office of Mayor Mitch Landrieu, Antenna, The Joan Mitchell Center, YAYA, the Arts Council of New Orleans and Prospect. In addition to his personal artistic practice, he currently serves as the Community Engagement Curator for the New Orleans Museum of Art. He has contributed to publications such as HuffPost, Burnaway and AFROPUNK, and his work has been featured by The Oxford American, The Associated Press and The Alternative UK. He is a recipient of several notable artist residencies and fellowships and most recently was selected as a 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Curatorial Fellow. He obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Morehouse College and a Master of Science degree from The University of Manchester (UK).

Nic Brierre Aziz’s Artist Statement

Up until the eighth grade, I was what one would consider an “exceptional student.” These years were spent in Catholic schools, despite my mother working as a social worker in public schools, and I always found myself at the top of my class. I was even skipped to the fourth grade less than two months into my third grade tenure because of my exceptionality – but despite this prowess, when I began the eighth grade at what was at the time considered the “best” high school in New Orleans, there was a colossal shift. Suddenly, my joyous, curious and intelligent being was thrown into an environment that was extremely destructive to my self-identity. This all-male 95% white catholic space was a treacherous jungle for anyone who did not fit this homogeneously rigid mold – and my boldly Black facial and cultural features along with my “weird” last name were as arguably as antithetical to this environment as one could get. My uncomfortability manifested itself in barely maintaining a 2.0 grade point average and often finding myself in detention (known as “Penance Hall”) for infractions such as unshined shoes and crooked nametags. This internal and external feud became so serious that I would often come home to my parents and contest my inferiority by telling them that they had to “accept that I was mediocre and stupid.” This mental affliction was so debilitating that my vehement contention was being done with a mother who was born in the first independent Black republic in the world and a father who was a former member of the Nation of Islam. Thankfully, one of the costliest natural disasters in world history liberated me from this mental captivity and changed my life for the better. I would go on to have numerous life experiences that prompted me to go inward and accept the beauty of my individuality. This is an exercise that is exceedingly difficult for any human on this perplexing planet – but especially for “minority” individuals in a country that was built upon (and continues to exist upon) the literal devaluation of their lives. These tribulations and their relationship to identity, truth and liberation have as a result become fundamental to my interdisciplinary practice. One of the often overlooked aspects of white barbarism (more broadly referred to as “white supremacy”) is the mental impact of erasure and marginalization. Personal and collective revolution has always and will continue to exist within the utilization of underdiscussed narratives to reimagine more righteous futures. I seek to create work from the dark matter that uplifts and heals, while exposing truths that enable us all to tread down a more collectively harmonious path of liberation.

About Louisiana Contemporary

For the 2020 edition of the annual juried exhibition, Louisiana Contemporary, Presented by The Helis Foundation, guest juror René Morales, Director of Curatorial Affairs and Chief Curator at Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), has selected 55 works by 56 artists.

Ogden Museum first launched Louisiana Contemporary, Presented by The Helis Foundation, in 2012, to establish a vehicle that would bring to the fore the work of artists living in Louisiana and highlight the dynamism of art practice throughout the state. Since its launch, Louisiana Contemporary has presented 729 works by 450 artists.

This statewide, juried exhibition promotes the contemporary art practices in the state of Louisiana, provides an exhibition space for the exposition of living artists’ work and engages a contemporary audience that recognizes the vibrant visual arts culture of Louisiana and the role of New Orleans as a rising, international art center.

Learn MoreInterview by Kasey Uddo, Ogden Museum Graduate Assistant