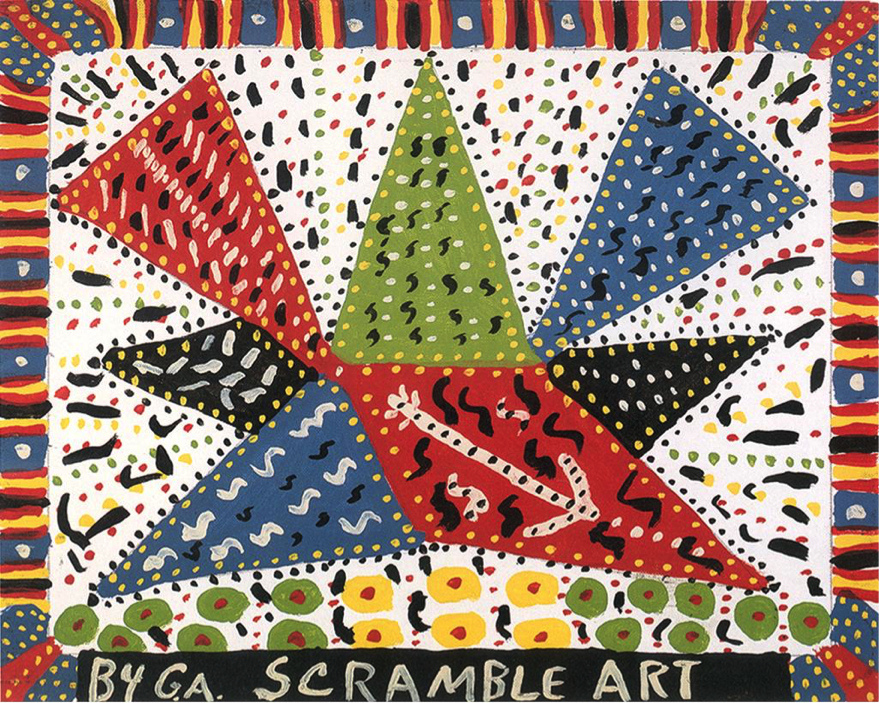

George Andrews, Scramble Art, 1989, Oil and collage, Gift of the Benny Andrews Foundation

On the surface, George Andrews (1911-1996) seemed to live a simple life, as far as artists are concerned. He was a family man, raising ten children, two of whom excelled following their passions of painting and writing. Artistically, he was known as the “Dot Man,” for his use of the simple shape both on the canvas and on everyday objects around town. And unlike his American and European contemporaries, who travelled the world in search of new sights and subject matter, George Andrews never strayed far from Plainview, Georgia- the rural town in which he was born in 1911 and was eventually laid to rest in 1996.

But the basic tale rarely tells the whole story, and to call George Andrews a simple man would be a gross mischaracterization. His son, renowned artist Benny Andrews, described his father as “peculiar… a very complex container of much more than the casual observer sees or hears.”[1] Physically, George was described as “impish” by journalists of the day, as his wiry frame carried no more than 100 pounds.[2] And as a mixed race man growing up in the middle of Jim Crow Georgia, Andrews dealt with terrorism and racism throughout his life.

Despite showing great creativity and promise from a young age, George Andrews was forced out of school and onto the sharecropping plantation by age 10.[3] He battled racism, poverty and other injustices his whole life, yet in the face of these and other challenges, George Andrews constantly fought back, using his art and creativity to persevere.

A great example of this battle can be seen in his relationship with his mother. Initially, his mother rejected his art, encouraging him to give up drawing and painting for reading and writing, especially while he was at school. But even after he left school to work in the fields, his passion for art remained. After his work days he would draw, and by the age of 10 he had taught himself to paint using a technique called “bluing,”which involved dipping a brush in cleaning chemicals in order to add color to the page. It was at this time that his mother began to accept, appreciate and even see the value in his art, and she allowed him to continue with his creations as long as they did not interfere with his work.[4]

“He [was] one of the most tenacious and imaginative persons I’ve ever met,” Benny said. “A personification of the mythical artist/poet who sees beauty through every pore, who is driven to create regardless of the circumstances.”[5]

At age 17, George Andrews married Viola Perryman. The couple had 10 children, and impressed upon their kids the importance of education. They encouraged their children to always be creative, no matter what the circumstances. Today, two of their children, Benny and Raymond, are nationally recognized artists (the former as a painter and the latter as a writer), and both cite their father as a source of inspiration and creativity.[6]

As an older man, George found an interest in the everyday objects around Plainview. He began by simply painting dots on rocks, but moved on to decorating furniture and other household items with shapes, dots, and bright colors. It was during this period that George Andrews began to receive recognition as an artist, and was donned “The Dot Man” by local Georgians.[7]

An example of the back and forth between simple and complex in the portfolio of George Andrews comes through his abstract work Scramble Art. Visually complex, the painting is a burst of color using the dots and lines for which Andrews is known. In terms of narrative, however, the work offers few clues toward any greater story or meaning. Like other great abstract works, we may never know exactly what this piece means (if it has a meaning at all), but something about the shapes, colors, lines, and dots tempt the eye time and again.