Ogden Museum of Southern Art

925 Camp St

New Orleans, LA 70130

504.539.9600 | HOURS

925 Camp St

New Orleans, LA 70130

504.539.9600 | HOURS

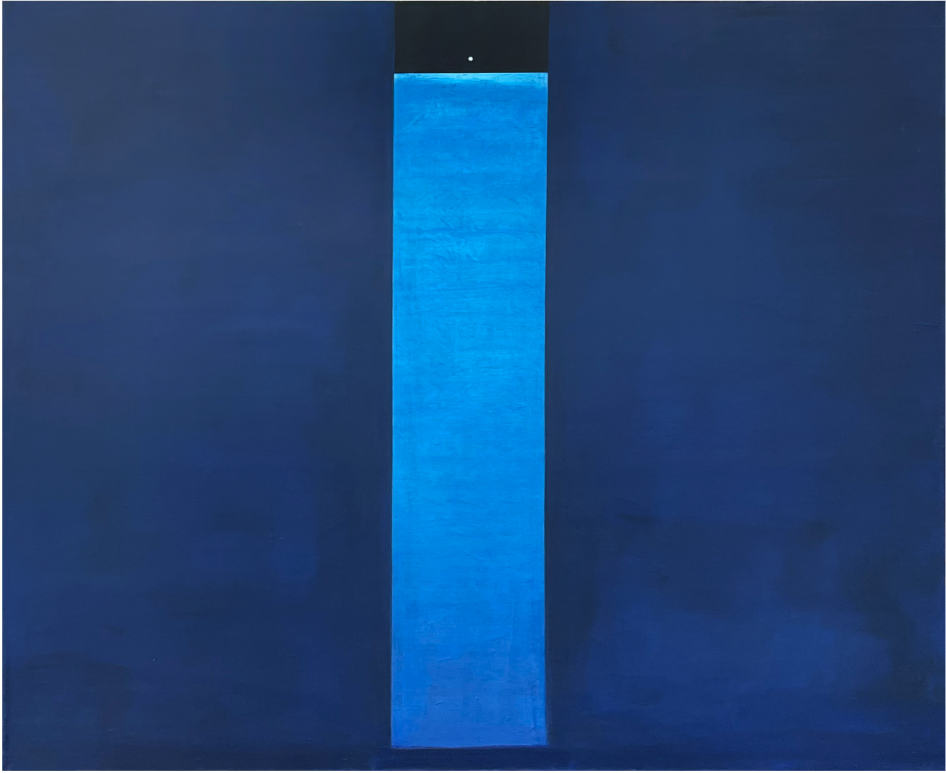

Edward Pramuk, Ice Rising from the Sea II, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 55 x 66 inches, Gift of an anonymous donor, courtesy of Ann Connelly Fine Art

The art of the American South has never existed in a vacuum. It has – since the earliest moments of the American experience – run concurrent with dominant academic art movements and popular trends, while maintaining a distinct regional identity. This exhibition traces the development of Southern Art through examples by leading figures working in the visual language of abstraction.

In the early 1940s, American Art took a new direction thanks to the innovation of loosely affiliated group of artists in New York City – the group of artist we now call the Abstract Expressionists, also known as the New York School. During and in the wake of World War II, as the US was forging a new direction for American life, these artists working in the language of abstraction were the vanguard of a new direction in art, a uniquely American style of art that would shift the avant-garde dialogue away from Europe. Through formal innovation and a focus on surface and process, this new style escaped adherence to realistic depictions of the outer world, seeking instead to convey the artist’s inner world. In the spirit of American individualism, these artists sought to create as a pure expression of self.

Abstract Expressionism was heavily influenced by another uniquely American musical form that had arisen from New Orleans a generation before – Jazz. These painters embraced Jazz as a guide to creation through improvisation, lyricism and spontaneity. Perhaps most importantly, these artists sought to reinvent the world with their paintings. Many had suffered through the Great Depression and witnessed the horrors of World War II. This new direction in art sought to explore the human psyche in pursuit of essential truth and to create a new direction in American culture, as well. Theirs was a mission of rebirth, innovation and hope.

The artists of the New York School came from diverse places. Some were Europeans seeking refuge from war. Some came from the Midwest, seeking work in the wake of the Great Depression. Some were native New Yorkers. Of course, there were Southerners involved from the beginning of the movement. New Orleans’ Fritz Bultman was a major figure in the first generation of AbEx artists. He studied under influential German-born American painter, Hans Hofmann, and was a member of the Irascibles, a group of artists who penned an open letter to the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, condemning the institution for ignoring a new American art movement. Another New Orleans artist, Ida Kohlmeyer, also made her way to the circle of Hans Hofmann. In New York, Hofmann persuaded Kohlmeyer to abandon realism in favor of abstraction. Kohlmeyer also met Mark Rothko, a leading figure in the New York School who was teaching in New Orleans, and whose influence would help move her work toward something wholly original in the history of American abstraction. Rothko also befriended and influenced New Orleans painter, Kendall Shaw. Shaw studied under Rothko during Rothko’s tenure as visiting instructor at Tulane University. Returning to New York, Shaw established himself first as an AbEx painter, then a founding member of the Pattern & Decoration movement. Mississippi’s Dusti Bongé had the rare privilege of being a part of the New York School, while living and working on Mississippi’s Gulf Coast. Beginning in 1939, Bongé showed her work regularly in New York City, most importantly at Betty Parsons Gallery, whose pioneering roster included some of the leading figures of the movement. Other artists from the South who participated in the New York School include Beauford Delaney from Tennessee, Jack Stewart from Georgia and Merton Simpson from South Carolina, among others.

Initially, the American South was less than receptive to the new movement of American art toward abstraction. But as Southern artists gained more access to education, both at home and afield, through the G.I. Bill, they were exposed to and trained in the dominant contemporary style of painting. Returning home, they brought more acceptance for abstract art to the South. Expanded funding for education by the federal government in the 1950s and 60s also played a role, bringing artists from Northern industrial cities into Southern art programs. Melville Price was one of the youngest of the first generation Abstract Expressionist circle of painters before moving to Tuscaloosa to teach at the University of Alabama. Tulane University’s art department – led by New Yorker Pat Trivigno – established an active visiting professor program, bringing established artists including Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still to New Orleans. Seymour Fogel – a leading figure in the New York scene and apprentice to Diego Rivera — moved to Austin, Texas in 1946 for a teaching position at the University of Texas at Austin. Thereafter, that University took the lead in the development of a Texas Modernist movement. As abstraction took foothold in the academic setting, appreciation for the style grew in the popular mind across the South. As new voices arrived in the South, others left for the larger Northern cities. Some artists stayed in the South, though, forging their own path. Three such artists were Bess Dawson, Ruth Atkinson Holmes and Halcyone Barnes. These women embraced abstraction in their studio practice beginning in 1951 in rural Summit, Mississippi. Showing together for the next three decades as The Summit Group, these rural artists exhibited in major museums across the Gulf South.

The dialogue of American Art is never stagnant, and while abstraction dominated the conversation for decades, it began to evolve in new directions. Abstract Expressionism led the way for a myriad of new movements including Post-Painterly Abstraction, Minimalism, Pattern & Decoration and Lyrical Abstraction, among others. Artists from the American South were involved with each evolution. Beginning in the 1950s, a group of mostly Southern artists in Washington, D.C., including Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, established the Washington Color School of painters, a group that was central to the larger Color Field movement in American Art. Eugene Martin developed his practice in this scene before relocating to Lafayette, Louisiana. Perhaps no other artist of the Washington Color School was more influential than Mississippi-born Sam Gilliam. Arising as a great innovator, his large unstretched Drape paintings not only challenged the traditions of his medium, but also the very spaces in which they were seen.

In the past few decades, abstraction has ceded ground to more figurative art in the contemporary dialogue. Yet abstraction is still very much alive, and relevant, as is evident in this exhibition. Artists such as John T. Scott, Ed McGowin, Clyde Connell and George Dunbar engaged in significant material exploration and meditations on regional identity with their work from the second half of the 20th century. Contemporary artists such as Shawne Major, Kevin Cole, John Barnes, William Monaghan and Sherry Owens continue to push conversation around abstraction into new territory with their work.

From early innovators in oil to the contemporary vanguard of material exploration, this exhibition traces Southern abstract artists’ impact upon a critically important movement – widely considered to be America’s most significant contribution to art history. By including both 20th century and contemporary artists, academically trained and self-taught – this exhibition considers the legacy of Modernism in the American South.

Bradley Sumrall

Curator of the Collection