Curator of Photography Richard McCabe discusses what sets Doris Ulmann’s work apart and how it resonates with people today.

Why did you choose to highlight Doris Ulmann’s work?

The work of Doris Ulmann is very important, and reflects part of our mission at the Ogden Museum. It is very interesting that she was from an upper class family in New York and went down to the South to make these images of working men and women.

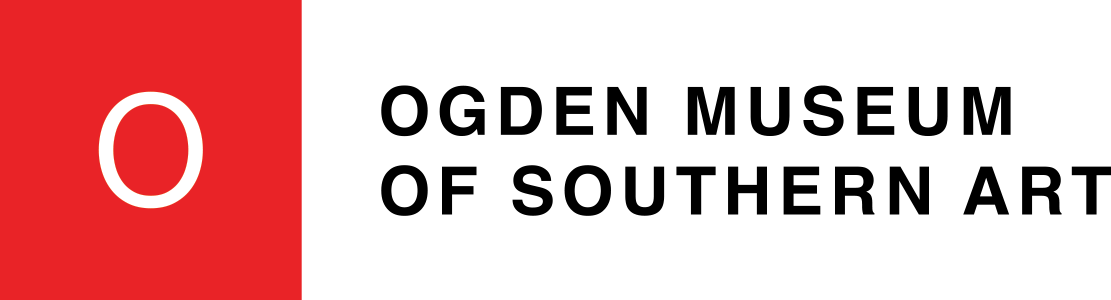

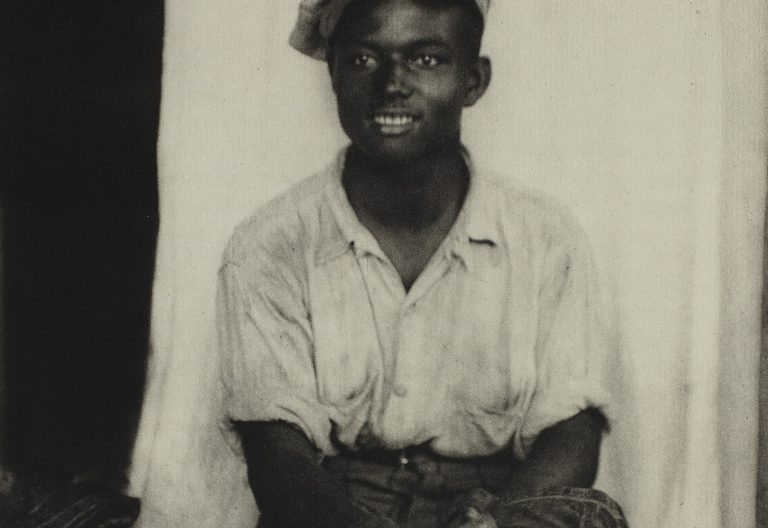

She was a famous portrait photographer, but also made these amazing images of just plain ordinary people from the South, using the same integrity that she used when she photographed people like Albert Einstein.

Do you think the themes and concepts in her photos would resonate with people today?

There’s a whole tradition in photography of bringing to light other cultures. I think people today would learn a great deal from Ulmann’s photographs. There’s a term used with photography, “exploitation,” like patronizing a subject, but there’s none of that in her work. It’s very positive, it’s very dignified. There’s a social quality to her work without being preachy or exploitative. If you look at new Southern photography, photographers are dealing with those ideas in today’s context. Kael Alford photographs native tribes in South Louisiana, who have been marginalized all their lives, and are going to be climate refugees because of rising sea levels. Another, Scott Dalton, deals with issues on the border, which is so pertinent to what we’re talking about now, and his very personal style of photography humanizes the people. I couldn’t go down there and make these images; none of us have the relationship with these people that these photographers are able to foster.

How do you think Doris Ulmann’s perspective as a native New Yorker influenced the pictures she took of people in the South?

People were using photography to elicit change in the world, and her political views were liberal and open-minded. She went to the Clarence H. White School of Modern Photography in New York City, which emphasized the importance of Pictorialism and informed how she viewed photography. At this point in the 1930s, when a lot of her work was made, Pictorialism was really out of vogue. She was interested in capturing people who might not have the means, but were proud of their work. How people were so tied to what they were doing, tied to the land or tied to their job. She was fascinated by how ingrained these ideas were in the South, and then showing those people in a positive light.

Ulmann was known for working with a large cumbersome camera and using older photo printing processes for the time. How did this influence her work?

Her methods glamourized her subjects, and made them more elegant. The ironic thing about the pictures is it’s obviously poverty stricken, but they’re in this beautiful, romantic, Rembrandt lighting. Her style might have softened the blow, and made it more romantic. There is a picture of a Baptism, of the Gullah folks, and it looks like they’re floating, like they’re saints. That would’ve been a very different picture if it was taken with a 35mm and silver gelatin print. It’d be a lot harder edged and graphic, where this is more poetic and metaphorical. Some photographers’ work is all about shock value, or “look at this tragic situation.” With Ulmann’s work, there’s never any kind of pity. It could be Albert Einstein, it could be a potter in North Georgia, she photographs the same way, with the same respect.

What went into opening this exhibition, and how long did it take, from the initial idea to the day it opened to the public?

We’ve been kicking around the idea for about five years and finally got around to it. I knew that Joshua Mann Pailet and Jessica Lange had a great collection and they were interested in showing it, so it was a matter of getting in touch with them and saying “yes, we’re finally going to do this.” Roger Ogden bought four last year at auction. I looked at them at New Orleans Auction House, and said I’d love to show them. I like to do three tiers of exhibitions. I like to focus on emerging young artists, who are maybe underrepresented. I love doing these Doris Ulmann shows—what I call the classics—and then blue chip, major photographers. She fits perfectly with what I’ve been trying to do as far as curating. The only way to learn about how photography got to where it is today is to look at people like this.

Was she able to see the recognition and respect she holds in the photography world while she was alive?

She was well-known, especially in New York as a portrait photographer, but not so much for this work she did in the South. She had done a few small periodicals in New York, like books of doctors. She was really into theater, so she photographed Lillian Gish, who was in “Birth of a Nation” and she was the biggest actress of the time. Ulmann was into theater, she was educated, she was into the finer things in life, so she had access to that.

I think her work resonates as much today as it did back then. She’s kind of like Eudora Welty because she has kind of a cult about her—people really love her work. She died pretty young, in 1934. They don’t really say how she died, it sounds like a heart attack, but she was in Asheville shooting for Southern Highlands. I think if she would’ve lived longer, she would’ve been more famous. She is known within the photography community and very respected. She’s well known, but maybe a little bit forgotten.

Do you have a favorite photo from the Doris Ulmann exhibition?

There’s one of a little girl with berries, it’s just so sweet. I love the guitar player. It’s just his eyes, it’s a little different than anything else. I love the baptism image of “Roll Jordan Roll,” there’s one of the people dancing. I guess what separates those is they’re not as posed, they’re more like people in the act of doing something. Those kind of resonate with me. They’re really sweet in that way, and elegant. I think they capture the gestalt of what she’s trying to do. Using the camera, the glass plates and her printing methods she was able to separate her look. Those all add up to very painterly, dreamy pictures.